Abstract

Noise pollution is a significant problem in the modern world, particularly in urban environments. In Europe, for example, more than 100 million people are exposed to harmful levels of noise pollution. Governments and local authorities have introduced extensive legislation to help mitigate this issue. For example, the United Kingdom has multiple pieces of legislation to help reduce noise pollution, such as the Noise Act of 1996 and the more recent Environmental Noise (England) Regulations 2006. Sound barriers along roads could reduce traffic noise. An experiment that I conducted showed that barriers between the receiver and the source of the sound decrease the overall recorded decibels. In the majority of cases, the higher the barrier and the closer it was to the source, the larger the reduction in recorded sound. However, residential areas, where these barriers would most likely be implemented, may have reservations about having a large concrete barrier between their homes and the road, regardless of the reduction in noise pollution. Therefore, further research into different materials, sizes and shapes is needed to understand the best way to bring them into suburban areas of cities.

Legislation

There is a substantial amount of legislation regarding noise pollution, with various rules governing industries like aviation. One of the primary pieces of legislation is the Environmental Noise (England) Regulations 2006, which mandates regular, detailed noise maps and action plans for road, rail, and aviation noise, as well as noise in large urban areas, such as new housing developments or supermarkets. This legislation is based on the European Environmental Noise Directive (Government of the United Kingdom, 2006).

Other laws, such as the 1975 Noise Insulation Regulations, which were amended in 1988, aim to reduce noise primarily from new or modified roads, focusing on areas with residential buildings. If there is at least a 1 dB increase directly resulting from the new or modified road, residential buildings within 300 meters of the development can qualify for noise insulation, including double glazing.

Additionally, the Noise Act of 1996 introduced penalties for excessive noise. There is a major emphasis on significantly reducing noise for dwellings between 11 p.m. and 7 a.m., and a local authority officer investigates any reported breaches during these hours.

Introduction

From cars to planes to the hum of a household fridge, the modern world is filled with machines and devices that produce noise, some more damaging than others. Therefore, when developments occur in the United Kingdom, especially in urban areas, noise pollution is analysed to ensure compliance with recent legislation.

There are significant problems with noise pollution worldwide, particularly in more developed nations. More than 100 million people in Europe, 20% of the continent’s population, are exposed to long-term noise levels that are harmful to their health (European Environmental Agency, 2024). One of the main culprits is the aviation industry, where noise is regulated to some degree at all airports in the United Kingdom, for example, and aviation flight paths are designed to fly over as few people as possible. Airports like London Heathrow do not allow flights to land between 23:30 and 4:50 to reduce overnight noise pollution, as, if the prevailing winds are correct, the landing path to the airport takes planes directly over the centre of London (Heathrow Airport Company, 2024).

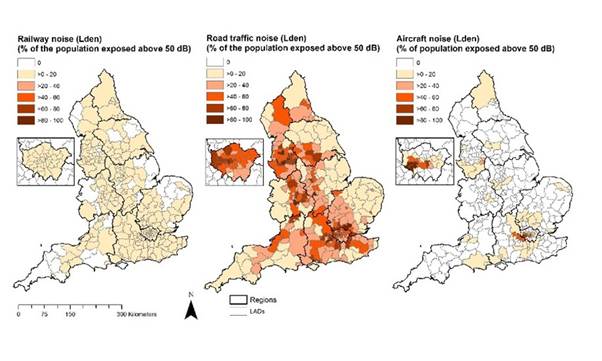

Figure 1 – Percentage exposure to railway, road, and aircraft noise pollution in England. Source: Government of the United Kingdom

Figure 1 outlines the percentage of railway, road, and aircraft noise exposure. Road traffic noise is the most common form of noise pollution to which people are exposed. Research by Kupcikova et al. 2021 concluded that exposure to noise pollution of over 65dB “was associated with small but adverse changes in blood pressure and cardiovascular biochemistry“.

With over half of the land in Great Britain being located less than 216m from a road, this information is concerning (Phillips et al. 2021). Therefore, with the rise of noise pollution in urban areas, mitigation strategies to reduce it are greatly important, and one such strategy is the installation of sound barriers along busy urban roads.

Methods

The following describes how to accurately measure the sound levels on a road or motorway and mitigate the impacts of possible noise pollution.

First, a background sound level must be recorded. However, the microphone must be located at the same distance along the road you are measuring throughout the investigation. Something as simple as 5 meters from the roadside would be sufficient as long as that distance can be accessed all along the road.

Next, multiple measurements at different locations along the location will be taken, and an average will be obtained from each area. Averages help improve accuracy as they reduce the impact of outliers, which may occur from a passing heavy truck or the call of a nearby bird in a nearby tree.

Once the background sound has been recorded, the next step in determining if there is a noise issue is to measure how much the sound levels reduce from the source and how much, if any, a barrier would reduce this volume. Take measurements directly next to the road or use a device that produces sound at different frequencies away from the road to understand better which barriers would reduce the noise levels the most. Once one of these sources is in place and switched on, noise pollution measurements will be taken at the same distance as the background levels were measured.

If using a source that can change the frequency of the sound it produces, change the frequency, note the decibel measurement on the microphone, and repeat for multiple different frequencies. For example, I used 125, 250, 500, 1k, 2k, 4k, and 8k. After the measurements have been taken, a barrier is placed between the source and the receiver, starting at either the most significant barrier, in terms of height, or the smallest barrier. Repeat the previous step of measuring the decibel level.

Data presentation

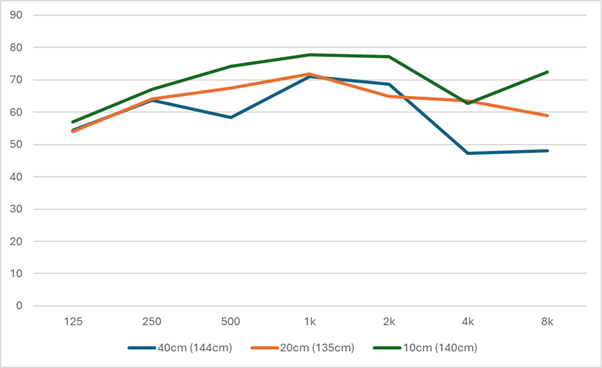

Figure 2 – Data from a 10-centimetre barrier with distance from the source plotted with decibels against frequency.

The 10-centimetre barrier offers some reduction to the noise levels, with the most significant decrease observed at the closest point to the source of the sound. However, the range between the data points is minimal at around 7.6 dB.

Figure 3 – Data from a 20-centimetre barrier with distance from the source plotted with decibels against frequency.

The graph showed more position changes at the 20-centimetre barrier compared to Figure 2, but the overall average is lower by around 5.3 dB.

Figure 4 – Data from a 40-centimetre barrier with distance from the source plotted with decibels against frequency.

Figure 4 showcases further decline, with the largest being at the closest point to the sound source and an average reduction from Figures 2 and 3 at -15.8 and -5.3 dB, respectively.

Figure 5 – Data from the closest points to the source in relation to the height of the barrier.

Figure 5 shows the height of the barrier at the closest point to the source of the sound, clearly showing that the 40 cm barrier demonstrates the most significant decrease in recorded decibels.

Figure 6 – Data from the middle point between the source and receiver in relation to the height of the barrier.

At the middle point between the source and the receiver, Figure 6 still follows the same pattern as Figure 5, with the 40cm barrier showcasing the most considerable reduction in recorded decibels.

Figure 6 – Data from the closest point to the receiver in relation to the height of the barrier.

The final figure once again shows that the larger the barrier, the greater the decrease in recorded decibels.

Discussion

In most cases, the most considerable reductions are found with the highest barriers and when they are closer to the sound source. Not closest to the receiver, this will be because the sound has more time to spread out… However, this experiment used a singular source, whereas major roads will have multiple, so the results would differ. Furthermore, the research was conducted in an anechoic chamber, so there were minimal echoes, which would not be the case in an urban environment, as houses are typically made of stone, which is not great at absorbing echoes. Therefore, more tests need to be conducted outside, next to major roads, to get a better understanding of how sound barriers may affect noise pollution reduction in urban areas.

Also, with the data showing that height is one of the main factors in reducing noise pollution, there would have to be a consensus on the maximum height to which roadside sound barriers should be. Would people, particularly in residential areas, want a 2-meter-high barrier regardless of what it is made out of near their home, or would they prefer a small one?

Another possibility is to use a more natural barrier, such as thick hedges and bushes. This would be more environmentally friendly and, considering the urban environment that they would most likely be in, would also look nicer than a concrete wall.

However, with the transition the UK government wants to undertake with moving everyone away from combustion engines and towards electric vehicles, is there still a need for sound barriers when the only noise that will be produced on the roads will be from the tires? Therefore, using different materials for the road surface for high-speed intercity roads would be a good step in reducing overall noise pollution. Yet resurfacing roads causes disruption and costs around £1 million per 1km of road (Government of the United Kingdom, 2023). The resurfacing of roads will help reduce noise pollution and save motorists as their cars will not have to deal with bumpy roads littered with potholes, which cost the economy of England around £14.4 billion and according to KwikFit’s annual report “Pothole Impact Tracker”, which estimates the yearly damage of potholes to vehicle, placed 2023 damages at £1.48 billion (Centre for Economics and Business Research, 2024) and (KwikFit, 2024). Nevertheless, in a world filled with so much noise, any relief may be welcomed by the communities next to major roads.

An investigation in North Carolina found a reduction of almost 15 to 50% of carbon monoxide and particulate matter as another bonus of having sound barriers along large roads (Baldauf et al. 2008). In comparison, other investigations have measured an average of 4.4 to 11.7 dBA at near-barrier points (Barros et al. 2024). This follows a similar pattern to the data I recorded in the anechoic chamber, further suggesting that a sound barrier would be a good mitigation for noise pollution in urban areas.

Conclusion

There is a significant amount of legislation that addresses the importance of mitigating harmful noise pollution. Sound barriers effectively reduce observed noise pollution levels, with a strong correlation between the size of the reduction and the height of the barrier. My research demonstrated a 15 dB decrease with the most substantial barrier, measuring 40cm, at the closest point to the sound source. Therefore, barriers between roads and residential buildings could be a viable solution to minimise the effects of noise pollution in urban areas. However, barriers can be quite unsightly, so in some locations, instead of a dull concrete block, wooden barriers or glass might be more visually appealing than concrete.

Recommendations

Further research is needed to better understand how barriers can reduce noise pollution. Investigating different materials as sound barriers is the next step to advancing their application in urban areas. Identifying which materials and shapes of barriers most effectively reduce noise pollution levels and determining the most cost-effective material represent critical questions that must be addressed.

Word Count: 1,945

References

Barros, A. (2024) Noise barriers as a mitigation measure for highway traffic noise: Empirical evidence from three study cases. Journal of Environmental Management. [Online]. 367, pp. 121963. Available from: <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.121963> [Accessed 03/05/2025].

Centre for Economics and Business Research (2024) The pothole crisis is costing £14.4 billion a year in economic damage in England alone. [Online]. Available from: <https://cebr.com/blogs/the-pothole-crisis-is-costing-14-4-billion-a-year-in-economic-damage-in-england-alone/#:~:text=KwikFit%20prepare%20an%20annual%20Pothole,damage%20for%20their%20service%20users.> [Accessed 03/05/2025].

Daldauf, R., Thoma, E., Khlystov, A., Isakov, V., Bowker, G., Long, T., Snow, R. (2008) Impacts of noise barriers on near-road air quality. Atmospheric Environment. [Online]. 42 (32), pp. 7502-7507. Available from: <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2008.05.051> [Accessed 02/05/2025].

European Environment Agency (2024) Noise. [Online]. Available from: <https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/topics/in-depth/noise?activeTab=fa515f0c-9ab0-493c-b4cd-58a32dfaae0a> [Accessed 03/05/2025].

Government of the United Kingdom (2006) The Environmental Noise (England) Regulations 2006. [Online]. Available from: <https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2006/2238/contents> [Accessed 03/05/2025].

Government of the United Kingdom (2023) £8 billion boost to repair roads and back drivers. [Online]. Available from: <https://www.gov.uk/government/news/8-billion-boost-to-repair-roads-and-back-drivers> [Accessed 03/05/2025].

Heathrow Airport Limited (2024) Night Flights. [Online]. Available from: <https://www.heathrow.com/company/local-community/noise/operations/night-flights#:~:text=At%20Heathrow%20we%20do%20not,from%20landing%20before%2004:30.> [Accessed 03/05/2025].

Kupcikova, Z., Fecht, D., Ramakrishnan, R., Clark, C., Cai, Y.D. (2021) Road traffic noise and cardiovascular disease risk factors in UK Biobank. European Heart Journal. [Online]. 42 (21), pp. 2072-2084. Available from: <https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab121> [Accessed 02/05/2025].

KwikFit (2024) Potholes Cost Nation’s Drivers £1.5bn in Repairs. [Online]. Available from: <https://www.kwik-fit.com/press/potholes-cost-nations-drivers-over-a-billion-pounds-in-repairs#> [Accessed 03/05/2025].

Phillips, B.B., Bullock, J.M., Osborne, J.L., Gaston, K.J. (2021) Spatial extent of road pollution: A national analysis. Science of The Total Environment. [Online]. 773 (145589). Available from: <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145589> [Accessed 02/05/2025].

+ There are no comments

Add yours